Asylum policy in Canada has come under growing political scrutiny in recent years. While the country has long positioned itself as a leader in refugee resettlement—through programs like the well-known Private Sponsorship of Refugees (PSR)—increased attention has been paid to irregular border crossings and spontaneous asylum applications. These two forms of access to protection—resettlement and in-country claims—are often treated differently by politicians and commentators. But what about the public? Do Canadians, like their leaders, distinguish between these two modes of protection?

In a recently published article in the Journal of Refugee Studies, I investigate this question using original survey data from 2021, collected as part of a comparative study across several Western democracies. The Canadian data allow us to ask not what Canadians think about “refugees” in general, but what they think about the policies through which refugees are protected. This distinction is crucial. Much public opinion research in this area tends to collapse attitudes to policy with attitudes to people—risking what I call the “bogus-refugee pitfall”: inferring people’s attitudes to international protection from their attitudes to refugees, whose protection needs may be thought of as illegitimate. The approach I adopt in the article attempts to eschew said pitfall to directly examine Canadians’ support for two policy mechanisms: admitting refugees who have been vetted and selected by the UN (resettlement), and admitting those who arrive on Canadian soil and claim asylum spontaneously.

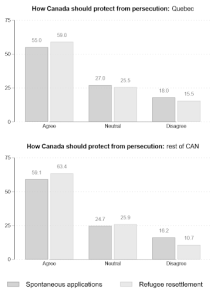

The findings are both encouraging and revealing. A majority of Canadians support both resettlement and spontaneous asylum applications. Support is slightly higher for resettlement—around 62%—than for spontaneous applications, which stands at 58%. Opposition remains a minority position for both policies. While media and political discourse around irregular crossings often imply a lack of public backing, the data suggests Canadians broadly accept both routes to protection as legitimate.

Source: Van Wolleghem (2025: 7).

What drives opposition when it does occur? Economic insecurity, employment status, or income level—typically assumed to fuel resistance to immigration—do not significantly shape attitudes toward asylum in Canada. Neither does political ideology: left–right self-placement does not predict support for either policy. This is a striking contrast with other countries in the study, where political orientation is more clearly linked to attitudes toward asylum.

Instead, the most consistent and powerful predictor of opposition to asylum policy is welfare chauvinism: the belief that public benefits should be reserved for citizens. In other words, Canadians who are less willing to share social services with refugees are more likely to oppose both forms of protection. This suggests that opposition is less about migration per se, and more about perceived entitlement. People are not necessarily concerned with the arrival of refugees, but with what their arrival implies for the distribution of social rights.

But public opinion is not monolithic. Roughly 22% of respondents show “dissonant preferences”: they support one policy but not the other. Some Canadians are comfortable with resettlement but oppose in-country claims; others support the reverse. This group is analytically interesting. What distinguishes them is not economic status or ideology, but institutional trust and views about international cooperation—although more research on this would be needed to consolidate the finding. Those who express higher trust in the United Nations are more likely to support resettlement, which is administered through UNHCR processes. Conversely, those who favour global collaboration on refugee issues—perhaps seeing asylum as a shared responsibility—are more inclined to support spontaneous applications.

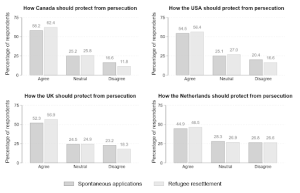

A final comparative dimension helps place Canada in context. Compared to respondents in the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands, Canadians are more supportive of asylum policy overall. But more importantly, the determinants of that support vary. In the three other countries, political ideology plays a stronger role in predicting asylum attitudes. Canada stands out in showing broad-based support that cuts across partisan divides. That said, welfare chauvinism operates in all four cases, suggesting a shared concern with fairness and entitlement rather than with cultural or economic threat.

Source: Van Wolleghem (2025: 15).

This research makes a conceptual contribution to the study of public attitudes toward asylum by shifting the unit of analysis. Rather than inferring policy preferences from attitudes to migrants or refugees—an approach that often confuses prejudice with principle—I look directly at support for the mechanisms of protection. Doing so reveals that Canadians are not simply “pro” or “anti” refugee. Rather, their views reflect more fundamental ideas about the state, about fairness, and about the responsibilities of citizenship in a global context.

At a time when asylum policy is increasingly politicized, this evidence provides a more grounded view of Canadian public opinion. While elites may frame irregular arrivals as a threat to order or sovereignty, most Canadians appear committed to the idea that protection is a core part of what Canada stands for.

Author: Pierre Georges Van Wolleghem – Research Associate Professor, NORCE Research; Research Associate, Department of Comparative Politics, University of Bergen; Research Associate, Centre for International Policy Studies, University of Ottawa