He was a felon with multiple criminal convictions, and they voted for him anyway. He prompted an angry mob to attack the Capitol and was described by his former Chief of Staff as having “fascist tendencies”, but they voted for him anyway. He consistently made xenophobic, misogynistic, hateful and fabricated remarks, and yet they voted for him anyway. Experts warned his proposed platform would harm the economy, damage the environment, and erode public health, but they voted for him anyway… Why?

For those of us who study the politics of climate change, the answer to this question could be helpful for figuring out how to get Western democracies to interpret climate change as the threat that it is, and to act upon this threat accordingly. In many ways, the rhetorical framing of a second Trump Presidency leading up to the election mirrors the rhetorical framing of Climate Breakdown: Generally speaking, the mainstream media, experts, and a large swathe of the population warned about a second Trump term as an existential threat to the country – a threat to democracy, to civility and accountability, and to human rights. At the same time, an alternative narrative, driven by right wing media networks and populist intellectuals, framed these concerns as overblown: Trump wouldn’t be so bad; he’d been in power before and democracy survived; and he ultimately offered a brighter vision of the future than his opponent.

Similarly, today we see the mainstream media, the expert class, and a large swathe of the population expressing deep concern about climate change, framing it as an existential threat – a threat to food security; to public health and safety; and to economic and political stability. At the same time, a rising alternative narrative, driven by right wing media networks and commentators frame these concerns as overblown: A few degrees of global warming can’t be that bad; our advanced industrialized society can easily adjust! After all, plants might even benefit from higher levels of CO2, and there will be less cold-related deaths!

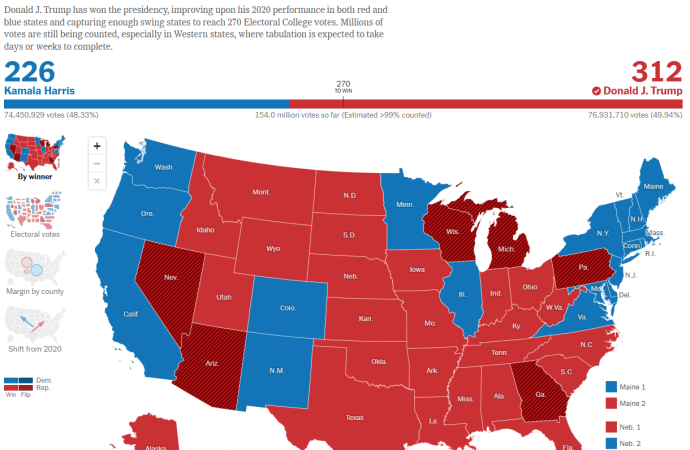

It is no secret which of these two narratives I find more compelling. As a professor who has studied climate change and society for years, the alarm bells sound with increasing frequency over the urgent need to halt global warming before various calamitous tipping points are breached. However, as a scholar who has approached this area of study through the gaze of political economy, I am painfully aware of the structural and social forces that historically have worked to stymie progress towards widely-held shared societal objectives like peace and stability and a sustainable environment. And so, the main questions for me since November 5th have included: Why did a majority of the electorate vote for this man, despite all of the widely-publicized damages that are expected to come alongside a Trump victory? Did they simply not believe the claims made about Trump? Did they believe the damages were worth it somehow? Or was there something else at play shaping how they interpreted what outcomes a second Trump term (or alternatively, a Harris victory) would have on their lives?

Since the election, the pundit class, Trump critics, and especially Democratic Party strategists, have all descended into a furious period of post-election analysis to figure out how and why this could have happened. Numerous theories have been proposed, generally falling into three main buckets: 1) it’s not that they were voting for him, so much as they were voting against her; 2) there was something he offered that people specifically wanted; 3) it was less about voting for or against one of the leading candidates, and more of a structural issue to do with America’s political economy or culture. The explanations span a range of issue areas, from desires for change; concerns about inflation; the Middle East; crime; concerns about wokeness or the taking away of freedoms; structural racism and sexism; and so on.

Whatever the reason, or combination of reasons, one factor that is not well explained is why all those 77.1 million Americans who voted for Trump were not deterred by the disqualifying nature of his candidacy and the threat he posed. And this, for me, comes back to the strategic lesson to be learned for climate communication: How do we get voters and political leaders to see climate change as the danger that it is? More importantly, how do we get them to prioritize this concern at the ballot box, or at the decision-making table, over other priorities? Social scientists who study climate change have puzzled over these questions for years. It is why we have debates about whether, for instance, carbon pricing ‘works’, or whether a favourable response is industrial policy; or hard cap regulations and product bans; or flexible regulations and voluntary measures; or consumer and corporate financial incentives; or whether litigation is necessary; or better educational campaigns; or smarter communications efforts and ‘nudging’; or counteracting misinformation; or more investment in research and innovation; or more fairly distributing wealth; or whether it is simply a matter of letting individual market priorities manifest through the invisible hand! Perhaps a deeper understanding of the US election outcome could help us get closer to some answers about how to galvanize climate action.

Recently, NASA’s Gavin Schmidt was rather direct in telling a journalist from The Guardian: “You shouldn’t ask [natural] scientists how to galvanize the world [to act on climate change] because clearly we don’t have a [expletive] clue.” Truth be told, while social scientists may have some clues about what galvanizes action, we are equally far from agreement on the most effective ways forward. As Trump’s electoral win and Harris’ loss suggests, social scientists continue to be puzzled by human behavior and the willingness of people in Western liberal democracies to vote against the interests and ideals of Western liberal democracy. Yet it is high time we figured it out, because while climbing back from an autocratic phase in American history is plausible, bringing Earth back from a hothouse state is not.

Ryan Katz-Rosene is Associate Professor at the University of Ottawa’s School of Political Studies and lives on a small family farm near Wakefield, Quebec. He thanks Luca Donais for research assistance in putting this article together